|

||

|

||

|

||

| Struck or cast coinage—the first form of ‘money’ as we know it today was invented in the early 7th century BC in Asia Minor and about the same time in China. An important aspect of this invention was that coinage was the first mass-producible medium of communication—a message could be reproduced exactly as intended in large quantities for distribution among a large audience for the first time. Very early on rulers began to realize the propaganda value of coins as symbols of power—the Kings of Lydia used the Lion and the Bull, symbols of their dynasty in the 7th century BC. Within 50 years the Greek City–States of Asia Minor and Greece proper had begun to produce their own coinages—each with their own representative symbols—a sea turtle for Aigina, the Pegasus for Corinth, Athena for Athens, a seal for Phokis, etc. These symbols were designed to be easily associated with the city that produced the coins—often they were puns on the city name or pictured the patron deity of the city. Soon tiny little towns with little political power and petty dynasts were issuing coinages as expressions of their independence. |

||

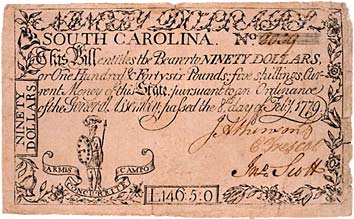

| This association of money with national sovereignty has continued to the present day, as witnessed by the insistence of new nations on producing their own paper currency and coinage almost before the institutions of State are fully formed. This despite the costs involved and the likelihood that the money will not gain much international acceptance—the important thing for these States is to get the message out that they exist and are independent. |

||

| The Romans developed the political use of coinage to unprecedented levels. Theirs was the first fully monetized society in the sense of money being used in the minor daily transactions of the majority of people. The Romans made full use of this huge audience through the development of a sophisticated, multi-faceted series of messages in writing and through symbols on their coinage. The messages were designed to support the Imperial government through expressions of the military prowess of the Emperor, the loyalty of the army, the happiness of the people, Imperial generosity and so on—the symbols used on these coins continue to be used today. After the fall of the Roman Empire, coins continued to be produced on the Roman model and the repertoire of symbols was retained and expanded. |

||

| Exhibit scope: | ||

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Objects: Examples of early coinages—Lydian, Greek, Chinese, Indian, Roman. Carry on with a discussion of the development and use of propaganda and “standard” symbols on coinage associated with royalty, sovereignty, personal freedom, etc. |

||

| Include examples of coins and early paper money produced by newly constituted nations (American Revolution, French Revolution, unified Germany, unified Italy, Ethiopia) followed by examples of money from recently formed nations in Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe.

|

||

| Historiographical Discussion: | ||

|

||

|

|

||

| Most general numismatic histories include a section on coin types in which topics such as propaganda on coins and the details and meanings of the images on the coins is discussed. This is not the same as discussing the history of the iconography used on coins to proclaim individual and national sovereignty, and how the act of coining or producing currency has been synonymous with an expression of independence since the earliest years of coinage in Ancient Greece. |

||

| Another point to make in the discussion of the following authors and their works (with the exception of some of the economists) is that they are overwhelmingly modern in their approach to history, mostly due to the nature of their evidence. Coins are among the most solid and enduring of primary documents and generally provide fewer problems of interpretation than comparable documents in other media. This is partly due to their small size, which limits the extent and complexity of their content, and also due to the fact that so many coins survive, allowing for comparison and checking of interpretations over large numbers of objects, something impossible in most other forms of written documentation due to their low survival rate. This is not to say that controversy and rival interpretations do not exist, but that they are largely concerned with appears on the coins as opposed to applying post-modernist ideologies to them. The changes which have occurred over the last century in Numismatic historiography have been concentrated in the area of technical knowledge of the coining process and the application of that knowledge in the form of die studies and the analysis of horde evidence. The research conducted in these areas has provided previously unavailable precision and insights into the dating of coins and their relationship to political and economic events testified to in other sources, as well as allowing for statistical analysis to illuminate otherwise opaque aspects of history. |

||

| A major reason for the lack of interest on the part of post-modernists in numismatics per-se appears to be the fact that the issuance of money has always been an “elite” activity performed by governmental authorities or large-scale merchants. There is little scope for re-interpretation of the purpose and use of money in the modern sense as invented by the Greeks, Indians, and the Chinese.

On the other hand, there is plenty of room for the interpretation of the uses and purposes of “traditional” money as used in sub-Saharan Africa, Oceania up until the mid–20th century, and the rest of the world prior to the invention or introduction of modern monetary forms. This is reflected in the virtual explosion of works on the subject of the symbols and forms of traditional money. This research has been appearing most frequently in anthropological journals and books since the 1970s, as well as in some economic journals. |

||

| Alfred R. Bellinger’s (1893–1978) article “The Coins and Byzantine Imperial Policy” includes a useful discussion of the iconography of the Byzantine coinage and its purpose. Bellinger distinguishes iconography of the court and that of the church on the Byzantine gold coins. Particularly interesting is his identification of the audience for the political and religious messages of the coins as the Byzantine bureaucracy and aristocracy. These audiences were the only part of Byzantine society to regularly deal with gold coins, and the rest of the coinage is largely static for long periods, reflecting a general indifference on the part of the Byzantine government in the opinions of the general public, a situation vastly different from that of the early Roman Empire. The bulk of the article discusses Byzantine history, using the coinage to highlight and illuminate imperial policy and pointing out where coinage anticipates the appearance of policy changes in other media.[2] |

||

| Andrew Burnett is the Keeper (head of Department) of the Department of Coins and Medals at the British Museum. Burnett’s book Coins: Interpreting the Past includes a useful discussion of the designs of western coinages through history. The book is primarily aimed at illustrating the importance of coins in the reconstruction of history through interpretation of their designs, inscriptions, physical characteristics, dating, and their find spots. Burnett begins with a definition of money and a discussion of the difference between simple lumps of metal (bullion) and coins. This difference is that coins are issued “with a recognized value by a competent authority.”[3] This definition serves as a jumping off point for discussions of state control of coinage systems and the purposes to which coins were put as a background for their potential as historical resources. |

||

| Frank van Dun is a Belgian philosopher who has written extensively on the subject of the principles of law and issues of taxation. He has a Ph.D. in the philosophy of law and legal theory from the University of Ghent, and is a lecturer there as well as at the University of Maastricht in the Netherlands. |

||

| Dr. van Dun’s article “National Sovereignty and International Monetary Regimes” is a philosophical tract dealing with the theoretical basis for National Sovereignty and how it is challenged by the development of supranational organizations such as the EEC. The article is set within the context of a book produced in order to combat what Dowd and Timberlake (the editors of the book) identify in their introduction as political interference in the national financial systems. The argument is that individual politicians through government powers enact misguided legislation for their own benefit that tends to undermine the stability of money, and thus the interests of the mass of people. The goal of the book is to advocate a monetary system constitutionally prescribed, operating under the rule of law and not subject to the whims of individual states or politicians.[4] Given the timing of the book, it is clearly aimed at influencing the development of the EEC’s financial institutions. |

||

| Michael Grant (1914–) is a renowned and prolific ancient historian with his early roots in the numismatics of the Roman Empire. He was born in London, England and educated at Trinity College, Cambridge. Among his many memberships and awards, Grant was President of the Royal Numismatic Society from 1953 to 1956, and has received the prestigious Royal Numismatic Society Medal. Grant pursued a career in academics and administration until 1966, when he began his career as a full-time writer. He currently lives in Italy. |

||

| Roman History From Coins is essentially a discussion of how numismatic data can be used to augment and broaden more traditional historical sources. Discussions include portraits of Augustus and Nero and why one should be remembered as the “pater patriae” of Rome while the other has been vilified by history. The discussions include useful information on the types of Roman coins and their relationship to state propaganda and glorification of the autocrat. The work is written using a modernist methodology; coins and primary documents are “facts” which can be used to illuminate or even discredit each other, thus Grant’s initial comparison of Nero and Augustus from evidence of the coins and from documentary and architectural remains—truly broad based research. |

||

| Philip Grierson was born in Dublin, Ireland in 1910 and received his M.A. from Gonville and Caius College at Cambridge. Grierson’s historical specialty has been Byzantine and Medieval European numismatics. He worked as an academic professor in England and Brussels before retiring in 1978 to pursue his own writings and research. Grierson is a past president of the Royal Numismatic Society (1961–1966) and a member of numerous other prestigious academic societies and organizations. |

||

| Grierson’s Byzantine Coins includes information on iconography, both religious and political and is considered to be a standard reference for the history of Byzantine coinage. It is a good source for the identification of symbols of sovereignty that influenced medieval Europe and the Muslim world.

|

||

| Sir George MacDonald (1862–1940) was the Honorary Curator of the Hunterian Coin Cabinet of the Fitzwilliam Museum. His book, Evolution of Coinage, is a concise discussion on the development of coinage. The book contains separate chapters for “Coinage and the States” (of particular relevance for this study) and for “Types and Legends” of coins up to the time of the book’s publication, though most of the examples are taken from the ancient world, MacDonald’s specialty. This book represents a refinement of the author’s previous thinking as presented in Coin Types: Their Origin & Development 700 BC to 1604. Numismatic historiography had not yet advanced to the stage of using die studies and horde analysis to date otherwise undated coins, but these techniques were in the first stages of development and were to come into their own over the next half–century. | ||

| George McDonald’s book Coin Types: Their Origin & Development 700 BC to 1604 is a collection of essays on the subject of coin designs delivered in the form of six lectures during 1905. The lectures were designed as an introduction to coinage design and represented a break from earlier thinking in numismatic literature because McDonald stressed that designs on early Greek coins owed more to identifying their place of origin than any to any commercial or religious connections. This debate reopened the problem of locating the mint cities of these ancient coins, thus focusing scholarship on an area that has made many of the advances in numismatic knowledge since 1905 possible. Mint identification using the designs of these early coins was complemented by the advent of professional archaeology based on scientific principles. Archaeology provided site finds of coins and hordes of coins associated with known and newly identified city-sites, plus the discovery of previously unknown city sites. All of this served to reinforce the political aspect of the production of coins. | ||

| Coins: An Illustrated Survey contains a wealth of images and articles by a variety of authors about coinages from all over the world—several of which have useful information on iconography. John Porteous is a numismatist well known for his general survey of numismatics entitled Coins: Pleasures and Treasures. Coins: An Illustrated Survey is based on the coin collection of the British museum, the foremost collection in the world. Martin Jessop Price, the editor, was the Deputy Keeper of the Department of Coins and Medals of the British Museum and a noted numismatic scholar of ancient coins as well as the Secretary of the Royal Numismatic Society. The authors of the book were selected for their expertise in various numismatic geographic and temporal specialties. John Porteous’ article serves as the introduction to the volume as a whole. The article has a concise discussion of the development and uses of money from its invention to the modern day, emphasizing the continuity over time of certain aspects of overall design and purpose. |

||

| Paul Romanoff (1899–1943) was a professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America with a background of studies in the Talmud and Mishna and a serious interest in numismatics. Dr. Romanoff was an alumnus of the Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning. Jewish Symbols on Jewish Coins is a specialized work on an area of numismatics rarely covered in such detail and is considered to be a classic in its field. The approach toward history in the book is modernist in that the author attempts to describe the types of Jewish coins as contemporaneous Jews understood them. He views coins as another source of information with which to reconstruct the psychology of the people of the past.[5] Despite conscious limitation of the scope to Jewish symbols on Jewish coins, Romanoff’s book goes beyond the specialized Jewish uses and meanings of the symbols covered, making it invaluable as a research tool for interpreting the ancient meanings for a host of types from palm trees to trumpets. |

||

| C. H. V. Sutherland was born in London, England in 1908 and earned a doctorate in literature from Oxford University. His professional career has encompassed numismatics primarily at the Ashmolean Museum as their Keeper of Coins but also included work as a lecturer at various institutions in the U.K. and the U.S. His major contribution to numismatics has been his editing and contributions to the first nine volumes of the Roman Imperial Coinage, the standard reference for the coins issued in the name of the Roman emperors. |

||

| Art in Coinage is mainly concerned with the artistry that appears on coinage from its invention to the present day (1956), as one would expect, but it also includes discussions about the purposes for the designs and inscriptions found upon coins. Sutherland states that the art appearing on coins is “a preeminently social art.” As such, he believes they reflect the spirit of their times and especially important as they are much more available than other sources of history. The primary characteristic of coins is their economic and social function, which requires that they constantly move through time and space.[6] Thus they are particularly suited for a specialized form of art and propaganda, which Sutherland elaborates as new aspects develop over time, from the first use of identifiable images associated to particular cities through the development of symbols with generally understood meanings and the use of inscriptions to convey political and religious messages. |

||

| Lawrence H. White is an associate professor of Economics at the University of Georgia. He earned his doctorate from UCLA in Economics. He is a prolific writer on the subjects of finance, market economies and banking. |

||

| Paul D. van Wie is Adjunct Associate Professor of Political Science at Hofstra University and is Commissioner of Landmarks and Historic Preservation, Town of Hempstead— Long Island, New York. Image, History, and Politics is an in-depth discussion of the coinage of modern Europe for the last two centuries beginning with the French Revolution in 1789. Van Wie covers each of the major European countries in seven chapters with discussions of the coin types and their symbolism. The questions of sovereignty and national identity and their representation on national coinages are dealt with as a central part of the book. The book is written in a straightforward modernist style, stressing evidence from the coins to illustrate the major political events of the times. The detailed discussion of the images on the coins makes this book particularly useful for the background of this exhibit. |

||

|

Bibliography: | |

| Bacharach, Jere L., “Dinar versus the Ducat,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1. (Jan., 1973), pp. 77-96. | ||

| Bellinger, Alfred R., “The Coins and Byzantine Imperial Policy,” Speculum, Vol. 31, No. 1. (Jan., 1956), pp. 70-81. | ||

| Burnett, Andrew, Coins: Interpreting the Past, Great Britain: University of California Press/British Museum, 1991. | ||

| Dun, Frank van, “National Sovereignty and International Monetary Regimes,” Money and the Nation State: The Financial Revolution, Government and the World Monetary System, Dowd, Kevin and Timberlake, Richard H., Jr. eds., New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1998. | ||

| Grant, Michael, Roman History From Coins, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1958. | ||

| Grierson, Philip, Byzantine Coins, London: Methuen & Co., Ltd, 1982. | ||

| MacDonald, George, The Evolution of Coinage, New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1916. | ||

| MacDonald, George, Coin Types: Their Origin & Development 700 BC to 1604, Chicago: Argonaut, Inc., Publishers, 1969 (reprint of 1905 edition). | ||

| Porteous, John, “The Nature of Coinage,” Coins: An Illustrated Survey 650 BC to the Present Day, Price, Martin Jessop, General Editor, New York: The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited, 1980. | ||

| Romanoff, Paul, Jewish Symbols on Ancient Jewish Coins, Philadelphia: The Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning, 1944. | ||

| Sutherland, C. H. V., Art in Coinage, New York: Philosophical Library, Inc., 1956. | ||

| Wie, Paul D. Van, Image, History, and Politics, Lanham: University Press of America, Inc., 1999. | ||

| White, Lawrence H., “Monetary Nationalism Reconsidered,” Money and the Nation State: The Financial Revolution, Government and the World Monetary System, Dowd, Kevin and Timberlake, Richard H., Jr. eds., New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1998. | ||

| Endnotes: | ||

| [1] Mattingly, Harold, Roman

Coins: From the Earliest Times to the Fall of the Roman Empire,

London: Methuen & CO LTD, 1962. p. 48. [2] Bellinger, Alfred R., “The Coins and Byzantine Imperial Policy,” Speculum, Vol. 31, No. 1. (Jan., 1956), pp. 72–73. Bellinger identifies the re-appearance of Christ on the coins of Theodora a decade or more prior to the re-introduction of icons into mosaics. [3] Burnett, Andrew, Coins: Interpreting the Past, Great Britain: University of California Press/British Museum, 1991. p. 10. [4] Dowd, Kevin and Timberlake, Richard H. Jr., Money and the Nation State: The Financial Revolution, Government and the World Monetary System, New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1998. pp. 1–2. [5] Romanoff, Paul, Jewish Symbols on Ancient Jewish Coins, Philadelphia: The Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning, 1944, pp. 5–6. [6] Sutherland, C. H. V., Art in Coinage, New York: Philosophical Library, Inc., 1956. p. 17. |